The Old Vicarage in Benthall

THE OLD VICARAGE, BENTHALL, BROSELEY, SALOP.

By JOHN SANDON

JOURNAL OF THE WILKINSON SOCIETY No. 6, 1978

Report of an archaeological investigation of the site, January 1978.

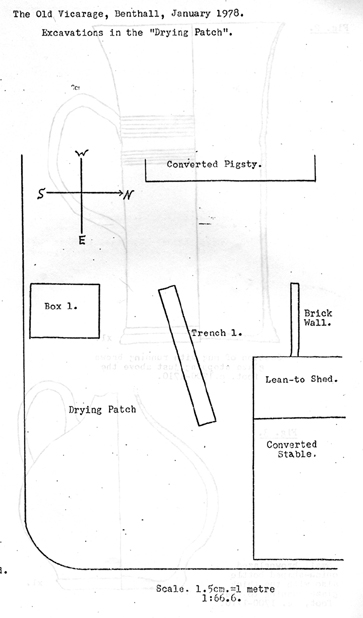

The Old Vicarage, Benthall, is situated just outside Broseley in Shropshire. The site is owned by Mr. & Mrs. Cragg and occupies two acres with a large brick house dating from about 1660 with later additions. North of the house is a slope leading down to a filled-in disused coal mine ventilation shaft of the early 20th century. To the south is a brick stable, probably the same age as the house, a lean-to shed attached to the stable, and a brick-built pigsty now used as a shed. These buildings form a division between the main back garden and a flat circular area bounded on the south side by a mixed hedge raised about 2 metres above a cow field belonging to a neighbouring property. (see fig. 1).

The house was mentioned in the 1851 census as Coppice House, Benthall and was occupied by Mr. Jones, a "Potter" employing several hands. It was used as a Vicarage in the late 19th century and hence received its present name. About 100 yards south of the aforementioned hedge during the 18th century were open-cast coalworkings known as the Deerleap. A wooden railway is recorded as having extended from the Deerleap to the main road through the Vicarage grounds.

Mr. Cragg recalls that up until about 15 years ago the flat area by the stable, known as the Drying Patch, was mounded up with an old bath, other bulky refuse, and material associated with early ceramics. These comprised a large quantity of saggars from a saltglaze kiln of c.1720, mostly imperfect, and pieces of saltglazed brickwork which were originally part of a kiln. However, all except a few complete saggars and one section of saltglazed bricks were dumped during the early 1960s to fill in the disused mine-shaft which had become unsafe. Other similar saggars had been used on part of the site just outside of the kitchen to support an earth bank which had been damaging a 19th century lean-to shed.

Considerable alteration to the site during recent years has resulted in many slopes and dips being repositioned. This makes it very difficult to determine the position of any demolished buildings. However, Mr. Cragg kept any pieces of ceramics uncovered during work on various parts of the site. It is impossible to say accurately the location each piece came from, except that all were from the site. These fragments, to be detailed later, give further evidence of salt-glaze and leadglaze manufacture, during the early 18th century, of types not normally associated with potteries in Shropshire, but typical of Staffordshire.

There is still much to be learnt about pottery making during this period, and so an archaeological excavation on the site was planned for early in 1978, in the hope of locating a kiln.

Henry and John Sandon, assisted by David Sandon, arrived at the Old Vicarage on December 31st, 1977 and after extensive examination of the locations decided the flat area known as the Drying Patch (fig. 1) would be the most likely place for a kiln to have stood, besides the fact that the saggars had been found there. If the circular area represented a kiln base it was felt a box would be best situated on the outer part of the Drying Patch just inside the south hedge, 200 cm. north/south by 150 cm. east/west. This we referred to as Box 1.

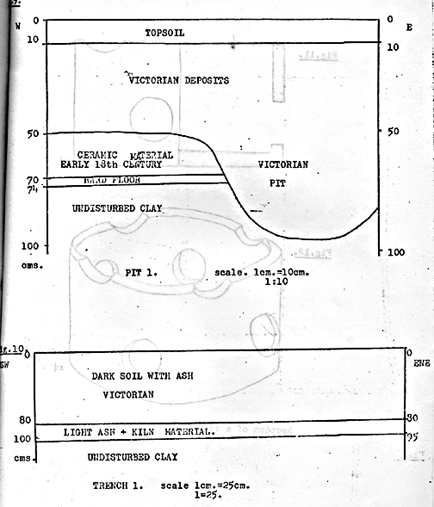

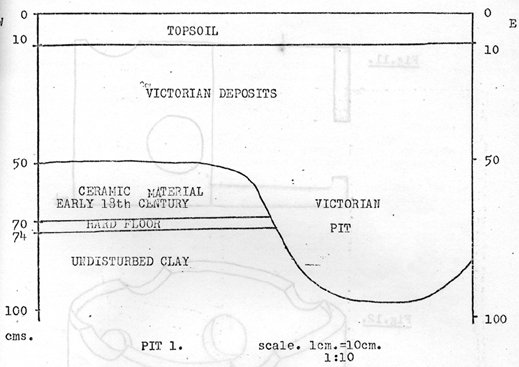

The topsoil was 10 cm. and contained very mixed dumps of recent ash and rubble, but also a few salt-glazed shards from the early 18th century, including wasters. This was termed level 1.

Below this was a wide deposit of dark soil representing general household refuse and deposits of Victorian and later dates. In the upper part of this level 2 were found a section of a salt-glaze saggar and other 18th century shards. Along with these were Victorian and 20th century pottery and glass bottles plus metal fragments, in considerable quantity. At about 50 cm. the Victorian remains died out and only 18th century fragments were found. All pieces were fragments and showed no signs of kiln imperfections.

At 64 cm. a fragment of flat unglazed high-fired earthenware was found with an incised name ? Clowlon and date 1 Octob.. . It is very similar in paste and colour to lead-glazed mugs found on other parts of the site. It is probably a potter's tool. At a similar depth was also found several unglazed shards possibly wasters, intended for glazing. One was clearly an unglazed fragment of a mug with turned banding exactly matching the mugs with brown lead glaze found throughout the site.

At 70 cm. a change of level was discovered; a compact earth floor of a lighter colour. On cleaning, a pit was found to be dug through the floor in the north east corner of the box. The pit contained a large quantity of clay roof tiles and a meat-paste container. The finds dated the pit to mid Victorian. At its deepest the pit reached 104 cm. from the surface.

The earth floor was a very compact layer of clayey soil containing rubble, cinders and pieces of early 18th century pottery. However, the floor was only a thin top shell lying on natural clay which was undisturbed. The clay was found at a depth of about 74 cm. and was white pipeclay stained brown with iron, containing varied sizes of pebbles. Box 1 showed no further prospects and after measuring was backfilled. A section is drawn as fig. 9.

The earth floor was a very compact layer of clayey soil containing rubble, cinders and pieces of early 18th century pottery. However, the floor was only a thin top shell lying on natural clay which was undisturbed. The clay was found at a depth of about 74 cm. and was white pipeclay stained brown with iron, containing varied sizes of pebbles. Box 1 showed no further prospects and after measuring was backfilled. A section is drawn as fig. 9.

The following day a further examination of the entire site was made with the help of Malcolm Nixon who is experienced on kiln excavation and structure. Again it was felt that the Drying Patch was the most likely site for a kiln.

Simeon Shaw in his "History of the Staffordshire Potteries" (1829), when debating the possibility of the Elers brothers making salt-glaze described the kiln said to have been used by the Elers at Bradwell in Staffordshire as being about 5 feet inside diameter, while salt-glaze kilns in Burslem were ten to twelve feet. He wrote ... "salt-glazed pottery of that time was comparatively cheap; and the oven, being fired only once a week, required to be large, to hold a quantity sufficient to cover contingent expenses. Hence we find the ovens were large, and high, and had holes in the domes, to receive the salt cast in to effect the glazing".

Box 1 had already ruled out a large kiln on the Drying Patch but a small kiln of say 6 or 8 feet in diameter could still have stood there. It was decided a trench nearer to the stable buildings might locate the foundations of a small kiln.

On Monday January 2nd 1978, John Sandon, Malcolm Nixon and David Sandon marked out a trench running NE/SW, 420 cm. long and 50 cm. wide. The thin turf lay directly on a dark ash and soil similar to the upper levels of Box 1. This represented a Victorian and early 20th century refuse dump probably associated with the house. It contained various glass bottles, metal tins and broken pottery, including several pieces of "Salopian Art Pottery" made nearby in Benthall c. 1900, and Coalport china from just over the river.

The dark rubbish level reached a depth of about 80 cm. before giving out to a pure ash level composed of grey ash and cinders with pieces of potter's tools and kiln furniture. They were of a type associated with the later 19th century. At between 95 and 100 cm„ the natural undisturbed clay was once more discovered ruling out the Drying Patch as the location for a kiln. The trench was back filled. A section is drawn as fig. 10. The kiln furniture probably represented the period when the house was used by Mr. Jones, c. 1850s.

The dark rubbish level reached a depth of about 80 cm. before giving out to a pure ash level composed of grey ash and cinders with pieces of potter's tools and kiln furniture. They were of a type associated with the later 19th century. At between 95 and 100 cm„ the natural undisturbed clay was once more discovered ruling out the Drying Patch as the location for a kiln. The trench was back filled. A section is drawn as fig. 10. The kiln furniture probably represented the period when the house was used by Mr. Jones, c. 1850s.

The failure to find any brickwork or traces of kiln structure indicated that the Drying Patch could never have been the location of a kiln. Therefore a further examination of the area was made to try and find a stratified undisturbed deposit of early 18th century material to help determine what ceramic use the site had been put to.

Just outside of the kitchen window above the lean-to previously mentioned is a mound bearing an oak tree and seeming to have been built up artificially. The tree appears to be at least 200 years old. A gentle probe under the surface produced a quantity of early salt-glaze wasters and so a small box was prepared.

The top 15 cm. was a very dark ash soil containing fragments of the salt-glazed saggars, pieces of "white-dipped" salt-glazed mugs and salt-glazed wasters, all c. 1700 - 1720. But this was only a surface dumping and lay on a thin level of brown soil containing household deposits of pottery and bones of the later 18th century. At only 25 cm. natural clay was again encountered. The salt-glazed level must represent a surface deposit of soil from another part of the site. Once more, after measuring, the box (Box 2) was filled in.

Box 3 was dug five metres south of Box 2, on a slightly sloping bank raised by a brick wall outside the back door of the house. Below the turf was a dark brown soil which gave on directly to the undisturbed natural clay, at a depth of 20 cm. Both Boxes 2 and 3 were 150 cm. by 100 cm,

No other parts of the site indicated from the surface that they might hide undisturbed levels of 18th century occupation, and so no further trial boxes were attempted. The only method which might be used to locate the kiln is a resistivity test of the ground using electrical equipment, and a test to be carried out, perhaps later in the year.

The only material which can be used to indicate what sort of pottery was made on the site are the saggars and the shards found by Mr. Cragg on unrecorded parts of the site.

There are three main types of ceramics found in quantity on the site, buff-coloured earthenware covered with a brown glaze, slipware fragments with various designs below clear glazes, and salt-glazed stoneware. Each will be dealt with in turn.

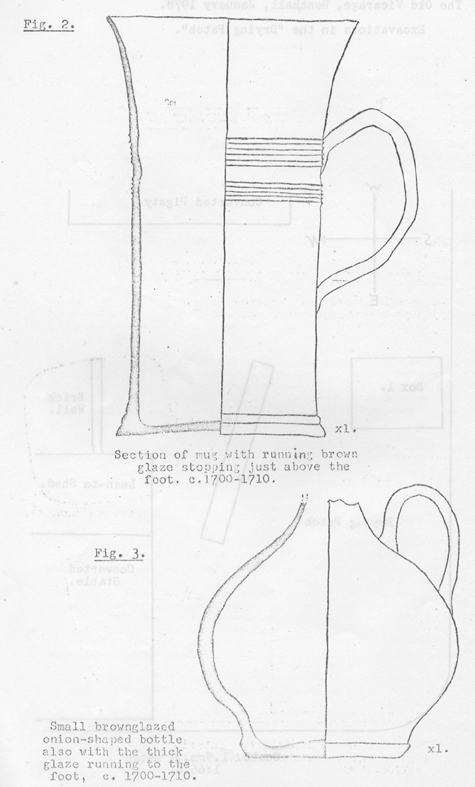

Most abundant are the brown-glazed wares of which over 400 fragments have been found. Mostly they are pieces of mugs, cylindrical at the bases and flared at the rims, particularly on the larger examples. The mugs occur in five different sizes and have slightly fluted curved handles roughly central on the side of the vessels. Just below the upper join of the handle are turned ridges arranged in two rows of four or five, running round the bodies, and each mug has turned ledges at the bases. From the base sections found it is possible to account for at least 25 different examples of the mugs. A typical example is drawn in section as fig. 2.

Most abundant are the brown-glazed wares of which over 400 fragments have been found. Mostly they are pieces of mugs, cylindrical at the bases and flared at the rims, particularly on the larger examples. The mugs occur in five different sizes and have slightly fluted curved handles roughly central on the side of the vessels. Just below the upper join of the handle are turned ridges arranged in two rows of four or five, running round the bodies, and each mug has turned ledges at the bases. From the base sections found it is possible to account for at least 25 different examples of the mugs. A typical example is drawn in section as fig. 2.

One unusual shape of which a nearly complete specimen and several shards were found, is an onion shaped bottle with a short foot and loop handle applied to the shoulder. The bottle's intended use is uncertain. Like the mugs, the small bottles are brown-glazed with the thick glaze dribbling to just above the foot (fig. 3.)

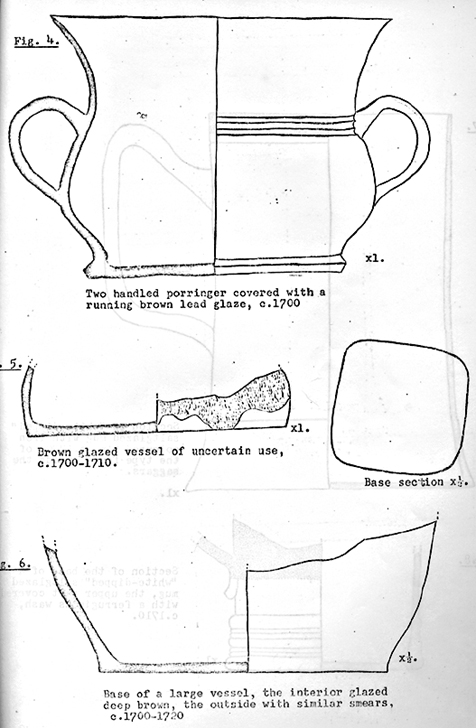

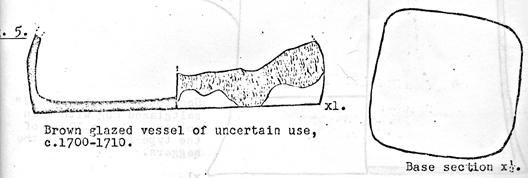

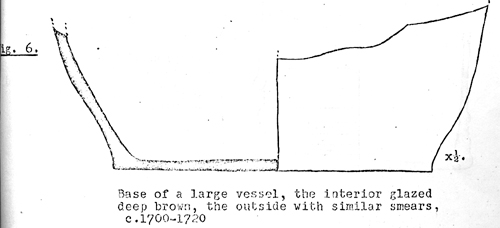

Other notable shapes in brown-glazed ware are a two-handled porringer with widely flaring rim and three deeply turned grooves level with the upper handle (fig.4.), the base of a very large bottle or cooking pot (fig. 6.) and a base of a flat or shallow dish of square shape with rounded sides curved both vertically and horizontally. It is not  possible to predict what form it originally took (fig. 5.).

possible to predict what form it originally took (fig. 5.).

There is very little evidence of kiln wastage among the brown-glazed shards found except for one mug base which has pieces of another not adhering to the inside, but it is not definitely a waster. The only certain  waster is the fragment found in pit 1, level 2, part of an unglazed mug with the turned bands. From the style of shape the mugs can be dated to c. 1700 - 1710.

waster is the fragment found in pit 1, level 2, part of an unglazed mug with the turned bands. From the style of shape the mugs can be dated to c. 1700 - 1710.

The slipwares themselves fall into two main types; variously coloured trailed and feathered designs in so called Staffordshire style, and a distinctive type of wares in fairly high-fired buff earthenware body, simply trailed in chocolate-brown with narrow bands and streaks,  below a pale yellow-tinted transparent lead glaze. The first type occurs in very small quantity and in scattered pieces not nearly complete enough to re-construct. These are probably imported dishes, maybe from Staffordshire, which were used and broken in the house.

below a pale yellow-tinted transparent lead glaze. The first type occurs in very small quantity and in scattered pieces not nearly complete enough to re-construct. These are probably imported dishes, maybe from Staffordshire, which were used and broken in the house.

Pieces of the other slipware type are much more numerous and some pieces are surprisingly complete. These include the base of a mug very similar in shape, and in a not unalike body, to the brown-glazed mugs already mentioned. Also a two-handled porringer related in shape to the brown-glazed one was found with brown streaks below a yellow glaze. The most impressive of this type was a complete but broken shallow dish of small size with a "piecrust" rim and parallel streaks of brown slip. Tests will be carried out on shards of both the brown-glazed and slipware pieces to see if, as suspected, they originated from the same clay.

The most important of the ceramic finds relate to salt-glazed stoneware production and from the finds a clear picture can be obtained.

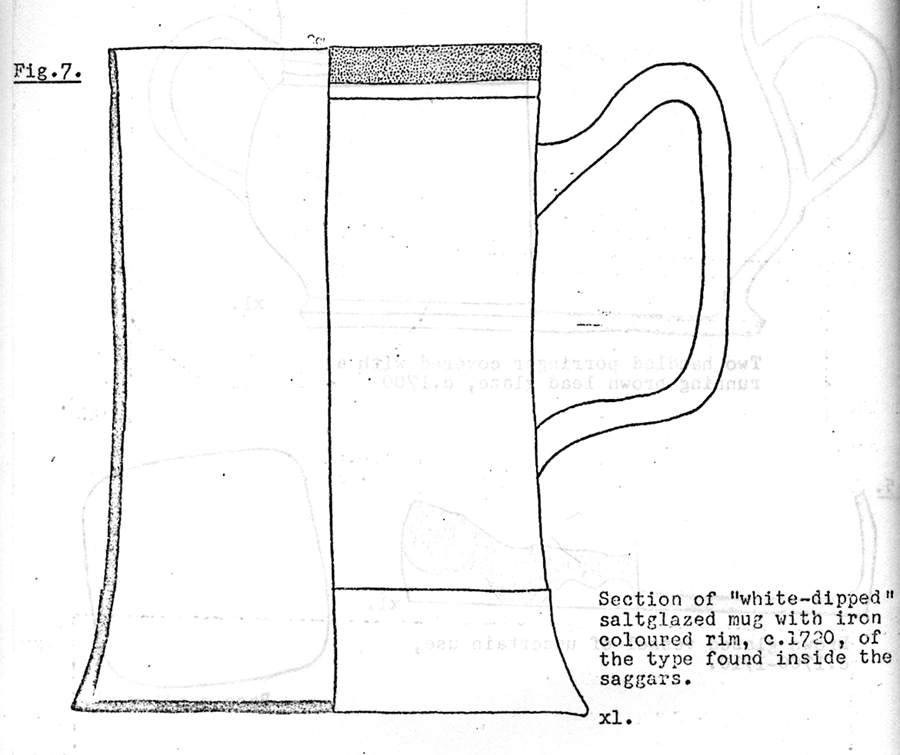

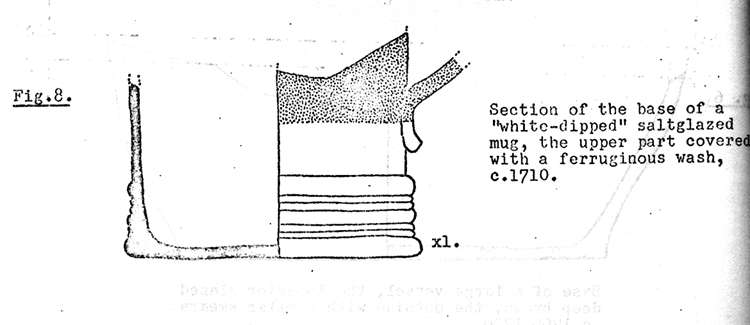

Salt-glazed wares developed in Staffordshire in a particular way. The earliest wares were brown using a clay rich in iron. Various experiments were made to try and introduce white salt-glaze but the white clay of Burslem was not suitable. It is said the Elers brother were first to overcome this by dipping their stoneware mugs into white ball clay imported from Dorset to produce "white-dipped" stonewares partly banded in brown. This process was introduced, whether by the Elers or by somebody else, about 1700.

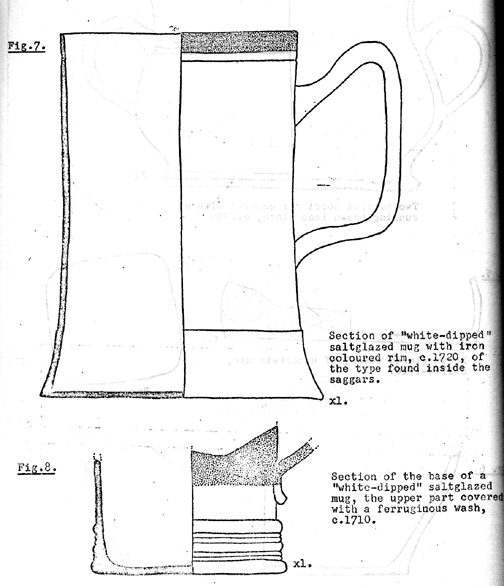

By about 1715 - 1720 a method was discovered by which the local clay could be whitened by adding crushed calcined flint. This gave the first true white salt-glaze and the process using calcined flints continued for many decades. Round about 1720 the rims of finely potted "white-dipped" vessels were dipped in iron which gave them a brown band around the rim. All pieces of these "white-dipped" salt-glazed wares are traditionally ascribed to Staffordshire, and so if the same sort of development can be found in Shropshire, traditional attributions will have to be re-thought.

By about 1715 - 1720 a method was discovered by which the local clay could be whitened by adding crushed calcined flint. This gave the first true white salt-glaze and the process using calcined flints continued for many decades. Round about 1720 the rims of finely potted "white-dipped" vessels were dipped in iron which gave them a brown band around the rim. All pieces of these "white-dipped" salt-glazed wares are traditionally ascribed to Staffordshire, and so if the same sort of development can be found in Shropshire, traditional attributions will have to be re-thought.

At the Old Vicarage site many fragments of salt-glazed stonewares have been found, a great number showing signs of being wasters. There are two sorts occurring, brown stonewares made from clay containing iron, and "white-dipped" wares, both with large brown  iron-coated areas (fig. 8.), and also with simple brown banded rims (fig. 7.). Some of the fragments have crazed on the surface, a feature common to Staffordshire wares.

iron-coated areas (fig. 8.), and also with simple brown banded rims (fig. 7.). Some of the fragments have crazed on the surface, a feature common to Staffordshire wares.

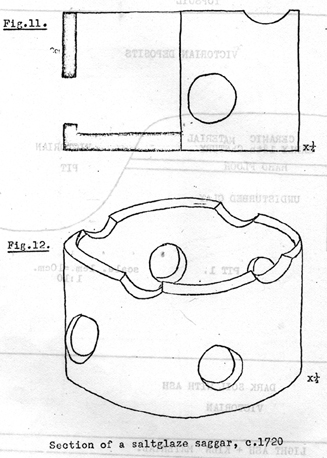

Of the salt-glaze saggars eight complete examples survive. They are circular drums with straight sides pierced with four round or slightly oval holes to allow the salt vapour to contact the pots during the firing. They are each about 38 cm. diameter, 20 to 23 cm. tall and the sides are 2 to 3 cm. thick. The top rims are cut with four shallow  curves to help separate saggars if they became stuck together in the kiln. Some of the saggars show signs of firecracks which have been patched with clay before being used again in another firing. Some have distorted and have had their rims reinforced to allow the next saggar to sit level. All the surviving saggars are heavily glazed with thick brown salt-glaze (figs. 11 & 12.).

curves to help separate saggars if they became stuck together in the kiln. Some of the saggars show signs of firecracks which have been patched with clay before being used again in another firing. Some have distorted and have had their rims reinforced to allow the next saggar to sit level. All the surviving saggars are heavily glazed with thick brown salt-glaze (figs. 11 & 12.).

Three of the saggars contain wasters of mugs stuck to the inside, with five or six bases arranged round one central one, the centre mug being smaller in size. The mugs are all of the type drawn as fig. 7. and have brown rims. Identical saggars have been excavated in Stoke dating from c. 1700 - 1720. The white mugs found inside the Benthall saggars date these examples to c. 1720.

To sum up, the ceramic material found on the Old Vicarage site in Benthall indicates local production of brown lead-glazed wares, yellow slipwares with simple brown streaking, and salt-glazed stonewares of brown and "white-dipped" types, all of the period c. 1700 - 1720. The quantity of material on the site, especially the bulky saggars, is conclusive evidence that the two kilns needed to fire the lead-glazed and salt-glazed wares were on the site or at least very near. The excavations in early January 1978 were unable to locate any kiln foundations but a further visit with resistivity testing equipment is planned.

The wares made during the early 18th century are of types known traditionally as Staffordshire and probably represent a group of potters migrating to the area from Staffordshire, remaining in touch with changes in production methods in Stoke. The site had ample supplies of easily dug clay and coal and, like in Burslem, the clay found on the site is rich in iron and would have produced brown salt-glaze until dipping in white clay was introduced. Very little true white salt-glaze was found and no wasters, and so it is quite likely that the introduction of calcined flint in Stoke, c. 1720, was an innovation not used at Benthall, and probably brought an end to the Benthall works.

Arrangements will be made to research the Parish and other records to try and find mention of a pottery on the site, and perhaps further excavation will be carried out later in the year. A saggar and representative fragments from the site are at present on exhibition in the Wilkinson Society Museum in Broseley.

References in this report to salt-glaze production in Stoke have been adapted from "Staffordshire Salt-glazed Stoneware" by Arnold Mountford which illustrates many pieces similar to those found at Benthall. I am especially grateful to Mr. & Mrs. Cragg for their kind co-operation throughout the excavations and for giving us complete access to the site.

John Sandon

A s t.